By: Jordan Folks

An equitable rate structure is one that does not require any customer segment to carry a disproportionate portion of the cost to serve while ensuring the service provider is able to meet grid demand and recoup the cost of energy procurement and delivery. It’s a tall order and one that must always be evolving, alongside the regulations, technologies, and the impacts of climate change experienced by utilities and other service providers and their customers.1

Utilities are finding that alternative rates (e.g., time-of-use [TOU] rates, time-varying demand rates) can motivate many customers to change their energy use behaviors to better align with grid needs. Ideally, these rates can be coupled with increased deployment of renewables and distributed energy resources (DERs) and decrease the need for peaker plants and traditional distribution upgrades. These time-variable rate structures deliver clear benefits for utilities, the grid, and certain customer segments; however, some utilities and customer advocates are concerned they may exacerbate the existing economic hardship of low-income customers.

Key Considerations When Designing Equitable Rate Structures

Alternative Rate Structure Options

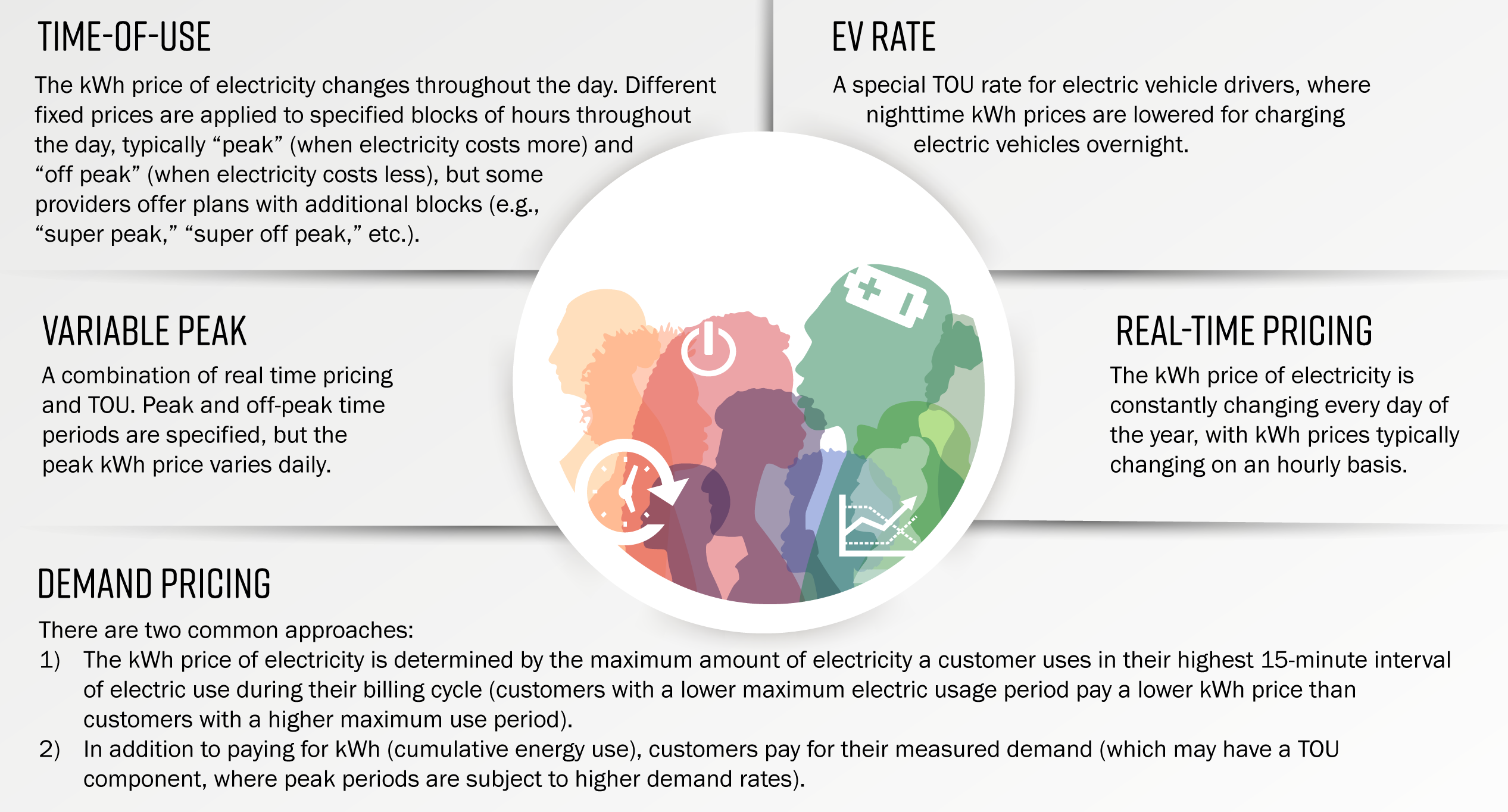

Equitable rate structures ideally provide cost and material benefits to all customer segments as well as utilities and the grid. There are a range of time variable rate structures, which can be used individually or in tandem, to encourage customers to reduce peak-time electricity use. Research conducted by Opinion Dynamics for the Smart Energy Consumer Collaborative (SECC) in 2019 explored some of the most common types of alternative rates employed in residential markets across the US to date. Figure 1 outlines and defines these alternative rate structures.

Impact of Volumetric Rates on Low-Income Households

Traditional volumetric rate structures, where everyone pays the same amount per kWh of electricity use, regardless of how much of their energy use occurs during peak vs. off-peak hours, may seem equitable; however, peakier users may not be paying their fair share. Households with flatter demand profiles and less energy use are considerably less costly to serve than peakier users. Yet, since all customers pay the same kWh rate, the customers who cost the least to serve effectively subsidize the energy costs for those who use more.

On a TOU rate, households with flatter load shapes will often see their electricity bill decrease because they are only paying the extra cost associated with peak time generation and delivery for the kWhs they use. Households with greater use during peak times will see their electricity bill increase in proportion to their above-average use of electricity during peak times.

While impoverished households tend to have flatter load shapes, other research has shown that despite successful demand reduction, substantial proportions of customers may experience increased bills on TOU pricing (given certain pricing, technological, or climate conditions). Clearly, the answer to the question, “Are alternative rate structures equitable?” is more nuanced than a decisive “Yes” or “No.” Household income level is only one of several predictors of electrical use and behavior as it relates to energy use.

Factors Beyond Income that Impact Low-Income Customers’ Relationship with TOU Rates

Awareness

The SECC study also explored consumer awareness of various electricity rates using a nationally representative sample of 1,138 of residential consumers. The study found that American consumers were moderately aware of alternative rates, although additional analysis found that surveyed low-income households tended to be less aware.

Awareness of traditional rate plans was similar across income categories, but low-income customers were significantly less aware of many alternative rate plans. Further, low-income customers were nearly twice as likely to be unaware of any rates- or event-based pricing mechanisms included in the survey. Awareness of one’s current rate plan was not differentiated by income status: similar percentages of low-income and non-low-income consumers claimed to know their current rate plan type (64% and 68%, respectively).

We also conducted evaluations of two alternative rate pilot programs that defaulted residential customers onto two unique TOU rates: one in California using TOU kWh pricing, the other in New York piloting TOU demand (kW) pricing. Despite significant direct-to-customer outreach campaigns, low-income customers were significantly less aware that they had been automatically transitioned to an alternative rate than non-low-income customers.

Preference

A choice-based conjoint study, one aspect of the SECC study, explored consumer preference for specific alternative rate plans. Of all demographics tested, low-income respondents demonstrated some of the lowest preference for alternative rates. Nonetheless, 56% of low-income respondents preferred a simple TOU rate with two tiers (peak and off-peak) with no demand charges and a $50 bill credit sign-on bonus over a standard rate, compared to 64% of non-low-income respondents.

Additional analysis found a striking difference regarding what constitutes an “ideal” rate plan across income levels. Respondents chose from rates with one of the following sign-on benefits: a one-time $50 bill credit, bill protection/price guarantee for one year, a rate comparison that shows what they might pay on the new rate plan compared to their old plan, and no sign-on benefit.

Low-income customers were significantly more drawn to the one-time $50 bill credit; simulations revealed that low-income respondents’ top nine most ideal rate plan configurations had a $50 bill credit, with the price guarantee included in the tenth most preferred rate plan. Conversely, non-low-income respondents’ second most preferred rate plan configuration included a price guarantee.

Our evaluation of a residential default TOU pilot conducted by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) found the preference for TOU rates grew considerably for both low-income and non-low-income customers after some time on the new rate. Preference for TOU rates among all segments reached an all-time high by the end of the one-year pilot.

Impacts of TOU Rates on Low-Income Households

In 2018–2019, PG&E conducted a default TOU pilot to prepare for a mass market default campaign. Approximately 150,000 residential customers were automatically transitioned onto a TOU rate in the pilot. We surveyed multiple waves of pilot participants, between ~2,000 to ~3,000 participants per survey. Analysis of billing data demonstrated a strong relationship between income and bill impacts from TOU rates.

Bill Impacts

At the end of the first year of the rate, achieved bill impacts far exceeded forecasts: nine out of ten low-income customers (90%) and over half of non-low-income customers (59%) benefited from the TOU rate, dramatically improving from modeled outcomes. Since predicted bill impact assumed no behavior change, improvements from predicted to achieved likely point to load shifting.

Behavior Impact

About half of low-income (46%) and non-low-income (50%) customers reported reducing or shifting their electricity usage over the course of the pilot. Low-income customers were more likely to report turning off home office or entertainment equipment, while non-low-income customers most often reported avoiding using larger appliances. Participant survey results suggest that barriers to effective load shifting were not uniquely tied to household income.

The results suggest most customers—regardless of income—are unlikely to face significant barriers to reducing or shifting their usage; all barriers were reported by less than one-third of respondents. Low-income customers were significantly more likely to report children or disabled persons in their household as barriers, although these were only mentioned by a minority of respondents. Non-low-income customers were more likely to cite working from home as a barrier.

Customer Satisfaction Impact

Low-income customers were significantly more satisfied than non-low-income customers with the TOU rate—and their utility—over the course of the pilot. Although low-income customers’ rate satisfaction dropped at the onset of the pilot, satisfaction levels rebounded by the end of the first year on the TOU rate. This finding suggests initial growing pains can smooth over once low-income customers have some time to adapt to the new rate.

Do TOU Rates Increase Economic Hardship?

Most low-income customers can save money on TOU rates. Further, over half (53%) of low-income customers who ultimately saved money after their first year on the rate did not report making behavioral changes. However, this year-end net benefit may require paying more in summer months and less in winter months (or vice versa in winter-peaking regions). Low-income households may struggle to afford the increased payments during summer months, regardless of the annual net benefit. But bill impacts alone cannot expose whether TOU rates cause economic hardship.

In 2016, California’s three largest investor-owned electric utilities (IOUs: PG&E, Southern California Edison [SCE], and San Diego Gas and Electric [SDG&E]) began opt-in pilots of residential TOU electric rate designs. Each IOU piloted two or three rates: each with unique peak pricing and timing. Our evaluation asked whether any of these pilots caused unreasonable hardship for economically vulnerable households or households with seniors.

We fielded two customer surveys, one at the end of the first summer and one after one full year on the TOU rates, to answer this research question: If vulnerable populations experience higher electricity bills under TOU rates, does this bill increase significantly worsen their economic well-being, or have a substantial effect on their economic livelihood?

PG&E and SCE households paid an average of $5–$40 more a month on a TOU rate during the summer than on a standard rate. Low-income customers tended to experience smaller increases than non-low-income customers. Most customers could only offset a small percentage of the summer bill increase via behavior change. Conversely, SDG&E customers experienced minimal structural impacts, with many customers offsetting bill increases via behavior change and receiving slightly lower bills during the summer period than they would have had on a standard rate.

Despite higher bills for PG&E and SCE customers, none of PG&E’s pilot TOU rates resulted in reported increased economic hardship. Conversely, 10% of segments treated in SCE’s territory (3 of 30) experienced increased economic hardship following the first summer of the pilot: all three were low-income segments in hot climate zones.

Mitigating Potential Impacts on the Most Vulnerable

The only limited evidence of increased hardship was found in hot climate zones, indicating TOU rates may be particularly problematic for low-income households that rely heavily on air conditioning during the summer. Billing data confirmed that comparatively lower bills in winter months offset the higher bills in summer months. While only one of SCE’s low-income segments demonstrated any statistically significant differences in economic hardship between treatment and control customers in the second survey, equitable rate structures must account for the most vulnerable.

In response to this study, the California IOUs took a myriad of preventative measures to ensure TOU rates would not overburden any low-income customers:

- Exempting low-income customers in hot climate zones from statewide default activities

- Providing baseline allowances for all-electric households

- Offering bill protection price guarantees

- Allowing customers to switch back to their previous rate at any time

- Launching educational campaigns about behavioral tactics to help keep bills down on TOU rates

Conclusion

TOU rates do not cause widespread economic hardship for California’s most vulnerable households, although their bills may seasonally increase on a TOU rate plan. There is a clear interaction between climate and income: only select low-income customer segments located in hot climate zones reported increased hardship via TOU rates. Additionally, this effect was limited to summertime and nullified after the subsequent winter and spring months—highlighting that these study findings are specific to California’s climate and technological environment.

Nonetheless, the study’s lessons are valuable across the US. Similar economic hardship outcomes may occur in extremely cold climate zones where residential electric heating is common. The interaction of rate structure, climate, income, and HVAC fuel type reveals an important policy implication; utilities planning to transition residential customers to TOU rates should consider implementing preventative measures that ensure low-income customers with electric HVAC systems in extreme climates are not economically burdened by the transition.

Although low-income customers may be less aware of alternative rates, our findings suggest TOU rates may be more beneficial than harmful for low-income customers. Our evaluation research reveals that low-income customers can make behavioral changes to shift their relatively flat load shapes, which are already predisposed to savings on a TOU rate. If anything, volumetric rates constitute an economic injustice to low-income customers, whereas levelized pricing inequitably penalizes those who can least afford to subsidize the peak-prone energy use of non-low-income households.

It’s time to harness the power of AMI, move beyond volumetric rates, and provide customers with more inclusive and equitable rate structures. Although customers may not see the immediate benefit, with proper education and outreach, many customers can become more active players in the energy ecosystem and ultimately benefit from alternative rate plans.

1 – While inclusive rate structures are possible across all customer segments, the scope of this article is limited to residential customers. Additionally, we recognize that true energy equity must include an assessment of multiple factors beyond rate structures and household income. We’ve limited the scope of this article to focus on equitable rates and pricing and the impact of rate structures on low-income customers, to engender greater specificity of our findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

For more information regarding the article, Contact:

Jordan Folks: jfolks@opiniondynamics.com

Related Content:

Article

Moving beyond “one rate to rule them all” -the equity case for TOU rates. By Jordan Folks & Alan Elliott

Podcast

Demand Rates – A Primer. Featuring Jordan Folks & Alan Elliott